Fighting bullying: how to measure teenagers’ evilness

Mythical characters like Darth Vader in Star Wars, Cersei Lannister in Game of Thrones or Thanos in the Marvel Cinematic Universe are proof that us humans, as viewers, believe evilness is made. We don’t like to think that there are evil people just because; we perceive a better written villain if their perversity comes from a hidden reason that justifies these actions. Was Cersei always mean, or perhaps her evident cruelty has been learnt along the way from those who surrounded her? Would she be better, had she been raised in the environment where Sansa Stark grew up?

What is evil? Is it possible to talk about it without analyzing contexts and motives people have?

Good and evil do not exist for me anymore.

Hans Bender (1907–1991), psychologist and doctor.

That’s how our Design Sprint starts, right after we were given the very difficult challenge of fighting the problem of bullying in Spanish high schools. This methodology, developed by Jake Knapp in 2010, was designed to find a solution and check its viability in only 5 days. The great advantage of Design Sprint? It allows to turn a complex goal into an affordable challenge in a very short amount of time, through the reformulation of objectives.

Part I: Understanding

In order to solve any problem, the first step is always understanding. The team began the phase of understanding in our Sprint by establishing a first general challenge, a long term goal: preventing bullying, focusing specifically on the bully.

From that idea, each member of the team developed a series of sprint questions, such as “Can we understand the reasons of the bully?” or “Are bullies aware that they are such?”. Altogether, the team established a total amount of 47 questions.

At this point, the team tried to empathise with all four parts involved in the bulling situation: the victim, the bully, the teacher and the psychologist in the High School. All of them are an active part of the scenario in which most cases develop. This step is really important to detect which questions are more relevan or decisive than others.

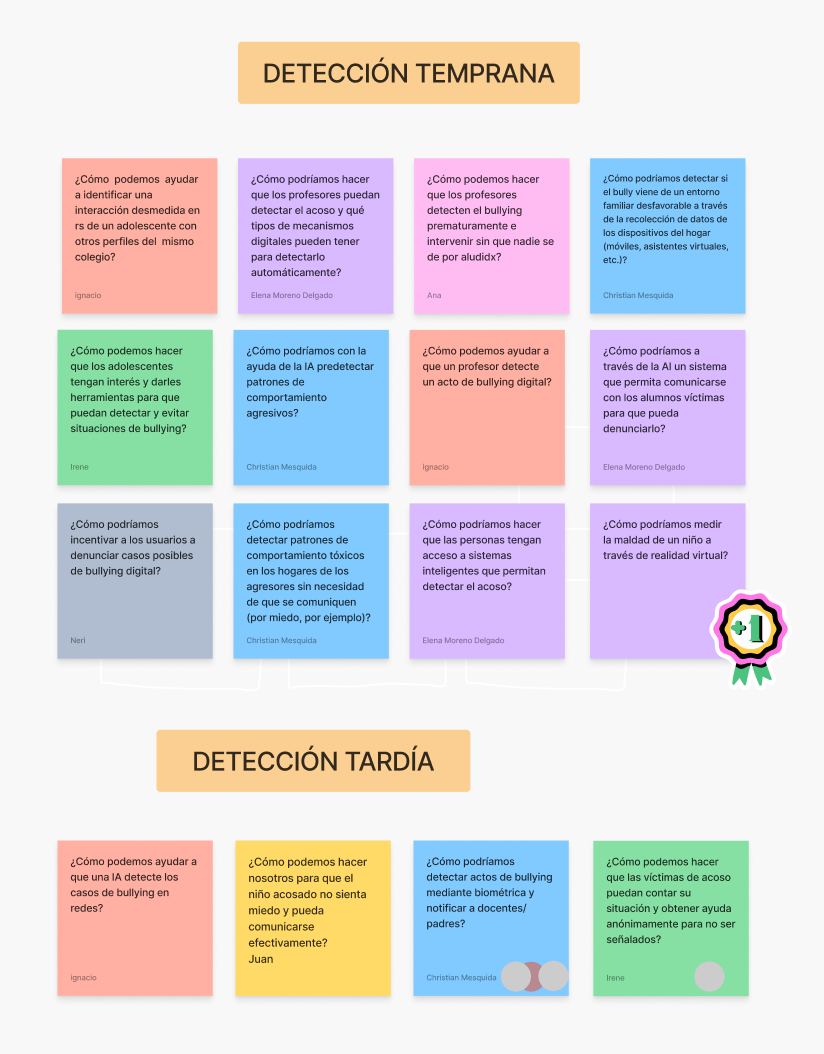

Once this empathy exercise was finished, essential to understanding the problem, we converted the Sprint Questions into How might we…?, turning every question into a call to action, each doubt into a potential solution. For a better organization, we classified the ideas in six categories and we chose through dotmocracy the ones we found to be more interesting.

The two favorite ideas were “How could we improve the relationship between teachers and students using AI or digital systems?” and “How could we detect evilness in a child?”. Here, the team was divided in two halves, depending on the idea we wished to develop. In my case, I was part of the evilness detection team.

To be wicked is never excusable, but there is some merit in knowing that you are.

Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) Writer and poet.

Part II: research

All ideation process must start with a good research, so my team and I conducted a very thorough benchmarking, in order to know which knowledge others had already found and which areas we were interested in exploring. We made a board and filled it with lightning demos, so that one person’s discovery was a whole team’s discovery. We found out that there’s a technology using virtual reality that measures the reactions of the kids in order to detect, for example, cases of AHDH, and we also learnt that there are videogames designed to know the personality of users.

Part III: ideation

Part III: ideation

The main challenge of this goal was detecting evilness in kids without them being cohibited in the process, which would lead them to change their answers and reactions. We’ve all done personality tests at some point in our liveas, and we all were very aware of what we were responding on each question. Every result, wheter we like it or not, it’s conditioned by social desirability bias.

But wait a second, what’s social desirability bias? It’s, basically, that little (or not so little) difference between what we really think, do, and are, and what we show to the world because we believe that’s what’s expected of us to do, to be accepted in society. We all do it, aware or not.

As first contact with the subject, we talked to an educational psychologist, Carla, who works along with high schools and universities as team coordinator. Her advice was demolising: “Look, just change the challenge”. We also contacted a high school teacher, Sara, who decided to ask her students why they thought people was evil. Here, we got a small insight, but a very important one: teenagers will tease you.

So, we found the hardest thing was to get data that weren’t distorted by the own subjects of the investigation. How can we measure teenagers’ evilness without them being aware of it? We needed something that could get their attention enough to make them take it seriously, but not so much that made them aware of it, so that results weren’t conditioned by the social desirability bias.

The team elaborated four proposals (one for each member) and we used dotmocracy to choose the solution we wanted to develop. The winner was a videogame that allowed the self-definition of the player, that placed them inside a story and that recopilated information of the way they behave so that it could establish patterns in their way of acting towards other people.

Part IV: the solution

Part IV: the solution

Reveal Yourself, the solution, is a narrative-oriented videogame that tells a story where the player is the main character. Since we don’t want players to see it as a totally fictional story (which would turn their participation into irrelevant), this story would include all the students in the classroom where we want to analyse the behavioral patterns.

Gameplay is choice oriented, so every player must decide between several options following their goals, and each interaction will have consequences in the story, both in the individual player’s story and the collective game story.

All these choices regarding themselves, the world and their classmates will collect data automatically that will be sent to the teachers, offering them the results regarding the pattern of their students’ behavior. For example, if one teenager tends to be leader in a group, the game will reflect it. If one student tends to isolate, it will reflect it, too.

Prototyping

Reveal yourself has two different interfaces, since the use for students is completely different than it is for teachers/educational psychologist. For teenagers it is a videogame and for educators it’s a database holding very specific profiles, whose strongest point is an extremely practical and visual display of the results that’ll make the information really accesible.

That’s why the first screen has to be a registration page, that’ll lead the user to the appropriate interface depending on their profile type:

Interface I: students

Since we didn’t have the means to design all the graphics for the videogame (yet), we used some screencaptions of one of our reference games, Life is Strange. That’s the only way we could recreate, fast and precisely, the idea we had of how the videogame should look and work.

One of the greatest points of this idea is the creation of a high quality videogame, not just a tool to detect the potential bullying patterns in a classroom. Only if we managed to get teenagers interested in the game we would get reliable results.

Interface II: teachers & educational psychologists

The teacher interface is built very differently, since the main functionality is not to be attractive, but useful, and to offer the results in a easy, simple, well-organised way. That’s why the information will be classified both by classroom and by student, offering also a graphic visualization and general ratings, just in case teachers don’t require concrete information from a student but the information of patterns in their classrooms as a whole.

The platform offers, for each user, a profile generated based on the choices and behaviors of the teenagers, and access to all answers given trhough the whole game story. It’s extremely important to take into account that these results have a margin of error, so it’s vital that teachers and psychologists can know exactly where this results come from.

Considering the time restrictions that come with Design Sprint, this prototype was made in medium fidelity wireframes. It’s also in Spanish, the team’s first language and the project’s target language.

Testing

Testing

As every good design challenge, the last phase of this Design Sprint was conducting some testing in a small sample of users, all of them somehow related to the relevant areas of our project. All of them were introduced in the concept and were showed both interfaces, so they could get a very thorough idea of the proposal, and were also asked to do a small usability challenge:

Generally, users thought the tool is useful, even though most of them doubted if students would take it seriously. Each tester had their own suggestions, but some of them agreed on including timed challenges to make sure the get into the game. The usability results were great.

After the testing process, two of the quotes we got from our experts stuck with us:

“It would be extremely useful to detect anomalous behavioral patterns”. Sara Romeo, high school teacher.

“It’s necessary that the teacher knows their students to know if they’re messing around or not”. José Luis Belmonte, high school teacher.

Iteration

Based on these results, the team found three simple iterations that would greatly improve the project: include a searcher inside the “My Students” page (improvement so big that we updated it on the previous wireframes), new pages offering information about the videogame and about the way it operates and, inside the game itself, time trial challenges that make teens function under pressure.

Conclusions

Conclusions

To be able to establish a final conclusion about the viability or non-viability of this project, main purpose of a Design Sprint, we value three key aspects: utility, usability and profitability.

- Utility: utility depends 100% on the attitude of the teenagers and the investment on the game.

- Usability: very positive, although there’s always room for improvement.

- Profitability: it would take a huge investment to carry out this project; it’s almost impossible that the investment turns out to be profitable.

This is why the team concluded that, despite the fact that the idea has been proven to be useful for the intended purpose, the low reliability of the results and the economic demand of this project make it not viable.